From the Botany & Horticulture section of our Unit meetings, and contributions from members...

Osmorhiza species, Sweetroot

A native herb with an anise-like fragrance

Osmorhiza species are anise-scented native herbs generally known as Sweetroots. In the Apiaceae Family, there are 8 species in the United States, two of which occur in North Carolina: O. longistylis, Longstyle sweetroot and O. claytonia, Clayton’s sweetroot. Of the two, O. longistylis has a more prominent anise scent, provided by trans-anethole which also dominates Pimpinella anisum, anise or aniseed.

Longstyle sweetroot grows in our area with leaves emerging in spring (sometimes well protected plants will survive the winter). They begin flowering in April with small white flowers that attract small bees and other early insects. They begin dropping seed during the summer or early autumn when temperatures are relatively warm to hot, which results in high germination rates the following spring. Some seeds will not germinate until the second spring.

They do well in rich, moderately moist, partly shaded spots, and will survive drought.

The root and leaf stalks have been cooked and eaten as a vegetable. The aromatic roots and unripe (green) seeds are used as an anise-like flavoring. The roots have been used for flavoring desserts and drinks or as tea.

The tender young stems make an excellent nibble while walking in the woods, and the young shoots and leaves can be eaten raw on salads or cooked. They have definite anise flavor, but can develop a bitter aftertaste.

We off no medical recommendations and suggest that if you decide to try some of the old medical treatments that you first contact your physician to make sure it will not interfere with any medicaitons you are using or conditions you have. Some old remedies have been found to be more dangerous than helpful.

The root (fragrant when crushed) has been chewed or gargled as a treatment for sore throats. A poultice of the moistened pulverized roots has been applied to boils, cuts, and sores. A tea made from the roots has been used to bathe sore eyes.

The article cited below studied seven plants known as sweet-tasting to test for sweetness comparable to sucrose, though the plants are not generally thought of as “sweet” in the same sense as sugar. Trans-anethole has been found to be nearly 13 times sweeter than sucrose at the concentrations in O. longistylis. “Thus, it may be concluded that the sweetness potency of trans-anethole when this compound is found as a major volatile oil constituent,” as in the “roots of Osmorhiza longistylis are…sweet tasting because of their high content of trans-anethole.”

Kathy Schlosser

Reference: Hussain, R.A. (et al) (1990). Sweetening Agents of Plant Origin: Phenylpropanoid Constituents of Seven Sweet-Tasting Plants. Economic Botany, Vol. 44, No. 2.

A native herb with an anise-like fragrance

Osmorhiza species are anise-scented native herbs generally known as Sweetroots. In the Apiaceae Family, there are 8 species in the United States, two of which occur in North Carolina: O. longistylis, Longstyle sweetroot and O. claytonia, Clayton’s sweetroot. Of the two, O. longistylis has a more prominent anise scent, provided by trans-anethole which also dominates Pimpinella anisum, anise or aniseed.

Longstyle sweetroot grows in our area with leaves emerging in spring (sometimes well protected plants will survive the winter). They begin flowering in April with small white flowers that attract small bees and other early insects. They begin dropping seed during the summer or early autumn when temperatures are relatively warm to hot, which results in high germination rates the following spring. Some seeds will not germinate until the second spring.

They do well in rich, moderately moist, partly shaded spots, and will survive drought.

The root and leaf stalks have been cooked and eaten as a vegetable. The aromatic roots and unripe (green) seeds are used as an anise-like flavoring. The roots have been used for flavoring desserts and drinks or as tea.

The tender young stems make an excellent nibble while walking in the woods, and the young shoots and leaves can be eaten raw on salads or cooked. They have definite anise flavor, but can develop a bitter aftertaste.

We off no medical recommendations and suggest that if you decide to try some of the old medical treatments that you first contact your physician to make sure it will not interfere with any medicaitons you are using or conditions you have. Some old remedies have been found to be more dangerous than helpful.

The root (fragrant when crushed) has been chewed or gargled as a treatment for sore throats. A poultice of the moistened pulverized roots has been applied to boils, cuts, and sores. A tea made from the roots has been used to bathe sore eyes.

The article cited below studied seven plants known as sweet-tasting to test for sweetness comparable to sucrose, though the plants are not generally thought of as “sweet” in the same sense as sugar. Trans-anethole has been found to be nearly 13 times sweeter than sucrose at the concentrations in O. longistylis. “Thus, it may be concluded that the sweetness potency of trans-anethole when this compound is found as a major volatile oil constituent,” as in the “roots of Osmorhiza longistylis are…sweet tasting because of their high content of trans-anethole.”

Kathy Schlosser

Reference: Hussain, R.A. (et al) (1990). Sweetening Agents of Plant Origin: Phenylpropanoid Constituents of Seven Sweet-Tasting Plants. Economic Botany, Vol. 44, No. 2.

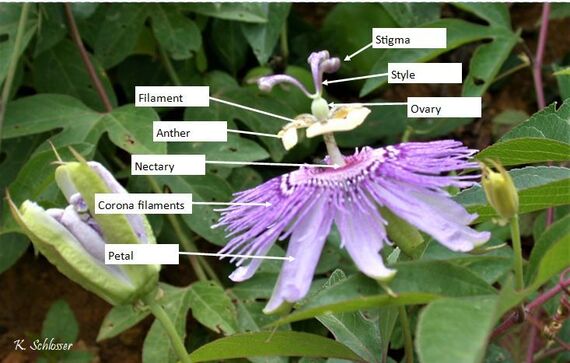

Passiflora incarnata, Purple passionflower or Maypop

We Would Love to Have You Visit!

|

|

LIMITED Permission to Use Materials

The right to download and store or output the materials on our website is granted for the user's personal educational use only. Materials are copyrighted may not be edited, reproduced, transmitted or displayed by any means mechanical or electronic without our express written permission. Users wishing to obtain permission to reprint or reproduce any materials appearing on this site may contact us using the Contact Form. If granted, we will email you a written permission for you to keep on file. We respond quickly to such requests. |

ASSOCIATION

The North Carolina Unit is a member of the Herb Society of America, Inc. Visit the national organization at www.herbsociety.org |